According to Israel’s Council for Higher Education (CHE), since 2011 the number of Arab students in Israeli universities has grown by 78.5% and currently just over 16% of the total student body is Arab.

According to Israel’s Council for Higher Education (CHE), since 2011 the number of Arab students in Israeli universities has grown by 78.5% and currently just over 16% of the total student body is Arab.

At Tel Aviv University, Arabs make up a visible and large minority, yet to me, an international student at the university last year, it was shocking to observe the degree of social separation. While overall the campus was more diverse than I had expected, lunchtime cafés and library study spaces were almost strictly divided places. Although supposedly a secular space, the university is home to the architecturally splendid Cymbalista synagogue yet Muslim students, who must pray five times a day, make do with a makeshift-mosque in a classroom.

In May 2018, I was a Masters student in conflict resolution at TAU, and a group facilitation course required us to organise an event which involved some of the key concepts we had been studying. We decided to try and do something to bridge the divide – or rather shrink the gulf – between Jewish and Arab students on campus.

The Muslim holy month of Ramadan, which sees a billion Muslims around the world fast during daylight, was just around the corner. Our programme director told us he thought an official Ramadan event had never before been organised on campus. At just the same time, I experienced the legendary Arab hospitality on a trip in the West Bank and started to notice how reluctant Arab students were to eat alone on campus. An idea was born.

The Iftar is the first meal of the day, eaten at sunset, and is a special time usually involving a feast with family. For many students living away from home for the first time, it can be a lonely time. An iftar which would be open to Muslims fasting, as well as Jewish students and anyone else, seemed to us like a great idea. As we began interviewing people to see how our idea would be received it soon became apparent that strong political currents invisible to us permeated student life as well.

We became aware that the Muslim Students’ Association was in fact organising their own events, separating men and women and not advertised to the wider (Jewish) student body. As I had decided to fast during Ramadan, partially in solidarity and partially out of curiosity, I was generously invited to the feast as well. It was a great experience but also a lonely one which strengthened my resolve to help host a more inclusive event.

At our event, we naïvely hoped that students of all backgrounds would simply eat together while learning more about each other, Ramadan and what it is like to be a fasting student in the Israeli summer. But much to our surprise, during our preparation several interviewees baulked at the idea of foreign conflict resolution students trying to bring together Arabs and Jews. A lot of people here cringe at the idea of another smartass from overseas trying to solve their problems and more than once I’ve been asked, “what does all this have to do with you, why don’t you leave us to it?”. For many Arab students, coexistence events are just a way for Jews to feel less guilty about the occupation, the full effect of which they don’t even understand. We had inadvertently stumbled into the complex world of ‘anti-normalisation’.

Even those who personally didn’t have a problem with our framing of the event strongly recommended that we be aware of this issue. Ultimately, we had to totally change the entire focus of the event. We removed any mention of ‘conflict resolution’. We removed any mention of ‘coexistence’. Our posters were in Arabic, Hebrew and English, but made no mention of the fact that we hoped plenty of non-Muslims would come. The focus was the food, leaving us to just facilitate conversations for any non-Muslims who came.

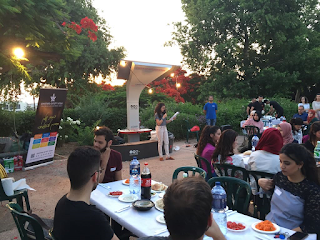

The event was a sell out several days in advance and in the end we received some really great feedback. Still, very few non-Muslims came. But I personally witnessed those that did becoming comfortable enough to have conversations about usually uncomfortable issues, wildly dancing dabke and making friends they continue to see to this day. Heartfelt thanks from Muslim students ended in more than more invitation to another meal together in the family home. Anti-normalisation didn’t put an end to the entire event but it revealed to me an aspect of the conflict that even studying conflict resolution hadn’t yet revealed

Ultimately, no matter what anyone feels about the merits of the movement, anti-normalisation is a powerful trend that so many good intentioned people both domestically and internationally don’t properly acknowledge or understand. It’s a feeling which won’t just go away on its own and as with everything, understanding why people feel this way is the first necessary step to do something about it.

Many thanks go to Professor Yuval Kalish, who preachers the power of conducting a conflict assessment before facilitating anything, in order to reveal precisely these kinds of important unseen currents; to Corey Gil-Schuster, who provided the initial inspiration for the event; and to Bassil Maroun, the legendary Arab Student Union representative without whom the event may well never have taken place.

_____

Alex originates from New Zealand, lives in Israel, and is currently exploring a career opportunity with Green Olive Tours. He recently completed his Masters Degree in Conflict Resolution and Mediation at Tel Aviv University.

Comment (0)